Teacher's Pet

“We want light-savers! Momma! I want the green one like Yoda the Master!”

“Momma, I want the red one! I’m Dark Vader, Sith LORD!”

“We are not buying toys today, guys. I have one more thing to get and we’re outta here. Please sit in the cart and make sure Momma doesn’t hit anything.”

I should have known better than to venture into Target on the Saturday after Thanksgiving, but damn it, the boys are out of pull-ups and I needed a shoe organizer for my closet—all sparkling clean and organized after a week of wardrobe purging.

I round the corner to head to the pharmacy and nearly run into another red plastic cart.

“Pardon me,” I say, flipping my cart to the left and pushing on.

“Not a problem, Madeline.”

I jerk to a stop. I don't recognize the voice, and hadn't even looked at the person pushing the other cart. I turn to look behind me and my heart does a little flip. It’s Max Piazza, my high school American Lit teacher.

Walt Whitman. Emily Dickinson. Nathaniel Hawthorne. Mark Twain. Harper Lee. Arthur Miller.

It was his second or third year teaching and I was completely out of my element, sitting in his classroom with twenty other students, the majority of who were bored stiff. They had little interest in or experience reading, much less discussing literature and poetry. He was enthusiastic about the material and tried to engage the students in every way possible.

I lived for that class.

Mr. Piazza was cool. Gum was allowed, and we could even eat and drink as long as it wasn’t a distraction from our shared purpose. Desks were optional. Most of the time I sat with Erin and Amber on the window ledge and Mr. Piazza and I waxed on about Huck Finn or Abigail Williams. Early on I knew I’d found a friend. He knew he could always count on me to have something to say.

He was tall and thin. His straight dark hair was gelled and spiked. He wore tortoise framed glasses and his adam’s apple moved when he spoke. I remember his chicken-scratch handwriting on the whiteboard (one of the first teachers to use one at our school). We had a relationship that he’s never had with a student since.

When I was in junior high, I lived in another state. I was in the honors program, which meant that I had the same English teacher from seventh to ninth grade: Mrs. Reese. She was the most amazing teacher. From the ages of twelve to fifteen I learned to read critically. I learned to write effectively. I learned that even the smallest observation was important when discussing Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl. I thought seriously about becoming a teacher.

My family moved the summer before I started high school. I got academically tested, joined the ranks of the honors students here and went about my business, thrilled that I’d found another English teacher who was as excited about literature as I was.

I had to leave early for a swim meet one day. Mr. Piazza wanted to discuss my paper on The Scarlet Letter. I arranged to meet with him the next morning before first period.

It was raining, and I arrived just after he did, shaking out his umbrella and wiping the mist from his glasses. I watched him hang his coat in the office and unbuckle his briefcase on the desk.

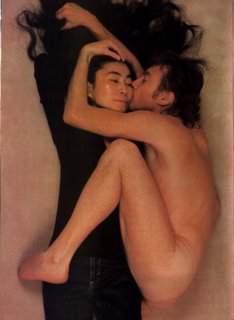

young teacher the subject of schoolgirl fantasy

“I have your paper, Madeline, and I have to say, it’s very good. I’m curious about why you chose to write about Pearl, Hester’s daughter, instead of Hester or Dimmesdale or even Chillingworth.”

Am I in trouble? Should I have focused on Hester? I swallowed.

“Well, as I say in the paper, Pearl is the most interesting character to me. She is the physical embodiment of the scarlet letter. Without her, it wouldn’t have existed. If Pearl hadn’t been born, no one would have known about Hester's adultery. She had this preconceived notion thrust upon her, and I think that we become that which is expected of us; what we expect from ourselves…and Pearl is a burden to her mother, something uncontrollable, just like the letter sewn onto her dress.”

He smiled, “I know. You’re the only student who wrote about that.”

“Maybe it’s because I have a close relationship with my mother. I mean, sometimes it seems like we are the same person, you know? So I think mother-daughter dynamics are interesting. I can see the unjustness of Hester’s situation, but I also see the unfairness of Pearl’s life, living in the shadow of something that never goes away.”

“I’m glad you’re in this class, Madeline. I’ve shared your paper with the Senior English faculty and they agree that you are insightful and talented…which junior high did you go to?”

“We just moved here; I went to junior high in Illinois. Springfield.”

“Not Jefferson Middle School?!”

“Yes! How do you know that?”

“I was a student teacher there a few years ago. Who was your English teacher?”

“Mrs. Reese…”

He shook his head, smiling, “I worked with her ninth graders in ’86.”

“I THOUGHT you looked familiar!” (Of course, I was in eighth grade and much too busy flirting with Jeffrey with the Flock of Seagulls hair to take much notice.)

“Tell me, and I know it’s three years ago and a long shot, but did you write an essay on Les Miserables?”

“yes….”

“It had to be you. You were the only Madeline in your class, right?”

“I was the only Madeline in the school. Why?”

“I read that paper. Mrs. Reese gave it to me. It was better than any of the Ninth graders’. She was really proud of you.”

So that sealed it. I was blushing and looking down at the tile, occasionally looking up at him, wanting to burst into laughter or tears. He knows me. He understands.

I missed Mrs. Reese; missed knowing that I could stop into her office anytime if something was troubling me and she’d put her hand on my arm and hug me and tell me everything would be alright.

Like the time my parents nearly split up and my mother told me after the fact that they’d even picked a day for my father to move out.

I was so upset and angry at her for doing that.

She sometimes forgot that I was her daughter, and not her best friend. So she confided in me.

When I was twelve.

I wanted to lean in, to put my cheek against Mr. Piazza (Max)’s chest and feel his arms cross behind my back. I wanted someone to understand that I was smart and observant and talented and not all together. I was sixteen. I wanted someone who understood and would be my friend.

So he understood. And he was my friend. Nothing inappropriate whatsoever.

Not that I didn't think about it.

I flirted shamelessly with him as high school girls do—at school dances, on Saturdays building sets for whatever play I was in, asking him to help me with the circular saw, feeling his hand guiding mine as we fed a piece of lumber forward—and if he was ever uncomfortable he never said so.

During college I babysat for his daughter. His wife was sweet, and the little girl wore a gold baby bracelet. I treasured her. I was thrilled to be in their home, happy to have an ongoing connection with him. And yeah, I had a fantasy that we'd have a hot affair when I was nineteen or so, and it would be a defining event in my life.

And even though that never happened, I know now that my instincts were right on about him. He was very attracted to me. If I ever had any doubts, they were dispelled when we stood, inches from each other in Target, while my boys bonked each other over the head.

He looks the same. The glasses are gone and he was wearing a baseball cap, and when I recognized him it was all I could do to keep myself from throwing my arms around him. He talked to my kids. He was truly sorry to hear about my divorce.

We chatted for several minutes. Occasionally I touched his arm for emphasis. Neither one of us knew how to end the conversation and continue with our shopping. Finally I gave him my card, you know, if he ever gets a free moment and would like to meet for coffee.

“That’d be great! I’ve thought about you a lot over the years—what’s going on in your life, that sort of thing.”

“That is sweet, and it means a lot to me. Thanks. It was so great to see you again.”

“Have a happy holiday, Madeline. Bye.”

As I strap the boys into their carseats, Miles asks me, “Momma, what was that man’s name again? Mr…..”

“Mr. Piazza,” I say as I pull out of the parking space and shift into first.

“Hahahah! I thought you were going to say his name was Mr. PIZZA!”

Miles and Jack are laughing in the back seat, repeating “Mr. Pizza, Mr. Pizza…Oh, do you know the Pizza Man, the Pizza Man, the Pizza Man….”

I shake my head, smiling to myself.

I turn on the radio, those adolescent thoughts still bouncing around my head.

And then I really lose it, listening to the song that haunted me through my teens:

She wants him, so badly, knows what she wants to be

“Pleeeease….dooon’t….staaand…..sooo…..clooose….tooo…..meee.”

sex sex blogs polyamory fantasies

parenting erotica sting the police

“Momma, I want the red one! I’m Dark Vader, Sith LORD!”

“We are not buying toys today, guys. I have one more thing to get and we’re outta here. Please sit in the cart and make sure Momma doesn’t hit anything.”

I should have known better than to venture into Target on the Saturday after Thanksgiving, but damn it, the boys are out of pull-ups and I needed a shoe organizer for my closet—all sparkling clean and organized after a week of wardrobe purging.

I round the corner to head to the pharmacy and nearly run into another red plastic cart.

“Pardon me,” I say, flipping my cart to the left and pushing on.

“Not a problem, Madeline.”

I jerk to a stop. I don't recognize the voice, and hadn't even looked at the person pushing the other cart. I turn to look behind me and my heart does a little flip. It’s Max Piazza, my high school American Lit teacher.

Walt Whitman. Emily Dickinson. Nathaniel Hawthorne. Mark Twain. Harper Lee. Arthur Miller.

It was his second or third year teaching and I was completely out of my element, sitting in his classroom with twenty other students, the majority of who were bored stiff. They had little interest in or experience reading, much less discussing literature and poetry. He was enthusiastic about the material and tried to engage the students in every way possible.

I lived for that class.

Mr. Piazza was cool. Gum was allowed, and we could even eat and drink as long as it wasn’t a distraction from our shared purpose. Desks were optional. Most of the time I sat with Erin and Amber on the window ledge and Mr. Piazza and I waxed on about Huck Finn or Abigail Williams. Early on I knew I’d found a friend. He knew he could always count on me to have something to say.

He was tall and thin. His straight dark hair was gelled and spiked. He wore tortoise framed glasses and his adam’s apple moved when he spoke. I remember his chicken-scratch handwriting on the whiteboard (one of the first teachers to use one at our school). We had a relationship that he’s never had with a student since.

When I was in junior high, I lived in another state. I was in the honors program, which meant that I had the same English teacher from seventh to ninth grade: Mrs. Reese. She was the most amazing teacher. From the ages of twelve to fifteen I learned to read critically. I learned to write effectively. I learned that even the smallest observation was important when discussing Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl. I thought seriously about becoming a teacher.

My family moved the summer before I started high school. I got academically tested, joined the ranks of the honors students here and went about my business, thrilled that I’d found another English teacher who was as excited about literature as I was.

I had to leave early for a swim meet one day. Mr. Piazza wanted to discuss my paper on The Scarlet Letter. I arranged to meet with him the next morning before first period.

It was raining, and I arrived just after he did, shaking out his umbrella and wiping the mist from his glasses. I watched him hang his coat in the office and unbuckle his briefcase on the desk.

young teacher the subject of schoolgirl fantasy

“I have your paper, Madeline, and I have to say, it’s very good. I’m curious about why you chose to write about Pearl, Hester’s daughter, instead of Hester or Dimmesdale or even Chillingworth.”

Am I in trouble? Should I have focused on Hester? I swallowed.

“Well, as I say in the paper, Pearl is the most interesting character to me. She is the physical embodiment of the scarlet letter. Without her, it wouldn’t have existed. If Pearl hadn’t been born, no one would have known about Hester's adultery. She had this preconceived notion thrust upon her, and I think that we become that which is expected of us; what we expect from ourselves…and Pearl is a burden to her mother, something uncontrollable, just like the letter sewn onto her dress.”

He smiled, “I know. You’re the only student who wrote about that.”

“Maybe it’s because I have a close relationship with my mother. I mean, sometimes it seems like we are the same person, you know? So I think mother-daughter dynamics are interesting. I can see the unjustness of Hester’s situation, but I also see the unfairness of Pearl’s life, living in the shadow of something that never goes away.”

“I’m glad you’re in this class, Madeline. I’ve shared your paper with the Senior English faculty and they agree that you are insightful and talented…which junior high did you go to?”

“We just moved here; I went to junior high in Illinois. Springfield.”

“Not Jefferson Middle School?!”

“Yes! How do you know that?”

“I was a student teacher there a few years ago. Who was your English teacher?”

“Mrs. Reese…”

He shook his head, smiling, “I worked with her ninth graders in ’86.”

“I THOUGHT you looked familiar!” (Of course, I was in eighth grade and much too busy flirting with Jeffrey with the Flock of Seagulls hair to take much notice.)

“Tell me, and I know it’s three years ago and a long shot, but did you write an essay on Les Miserables?”

“yes….”

“It had to be you. You were the only Madeline in your class, right?”

“I was the only Madeline in the school. Why?”

“I read that paper. Mrs. Reese gave it to me. It was better than any of the Ninth graders’. She was really proud of you.”

So that sealed it. I was blushing and looking down at the tile, occasionally looking up at him, wanting to burst into laughter or tears. He knows me. He understands.

I missed Mrs. Reese; missed knowing that I could stop into her office anytime if something was troubling me and she’d put her hand on my arm and hug me and tell me everything would be alright.

Like the time my parents nearly split up and my mother told me after the fact that they’d even picked a day for my father to move out.

I was so upset and angry at her for doing that.

She sometimes forgot that I was her daughter, and not her best friend. So she confided in me.

When I was twelve.

I wanted to lean in, to put my cheek against Mr. Piazza (Max)’s chest and feel his arms cross behind my back. I wanted someone to understand that I was smart and observant and talented and not all together. I was sixteen. I wanted someone who understood and would be my friend.

So he understood. And he was my friend. Nothing inappropriate whatsoever.

Not that I didn't think about it.

I flirted shamelessly with him as high school girls do—at school dances, on Saturdays building sets for whatever play I was in, asking him to help me with the circular saw, feeling his hand guiding mine as we fed a piece of lumber forward—and if he was ever uncomfortable he never said so.

During college I babysat for his daughter. His wife was sweet, and the little girl wore a gold baby bracelet. I treasured her. I was thrilled to be in their home, happy to have an ongoing connection with him. And yeah, I had a fantasy that we'd have a hot affair when I was nineteen or so, and it would be a defining event in my life.

And even though that never happened, I know now that my instincts were right on about him. He was very attracted to me. If I ever had any doubts, they were dispelled when we stood, inches from each other in Target, while my boys bonked each other over the head.

He looks the same. The glasses are gone and he was wearing a baseball cap, and when I recognized him it was all I could do to keep myself from throwing my arms around him. He talked to my kids. He was truly sorry to hear about my divorce.

We chatted for several minutes. Occasionally I touched his arm for emphasis. Neither one of us knew how to end the conversation and continue with our shopping. Finally I gave him my card, you know, if he ever gets a free moment and would like to meet for coffee.

“That’d be great! I’ve thought about you a lot over the years—what’s going on in your life, that sort of thing.”

“That is sweet, and it means a lot to me. Thanks. It was so great to see you again.”

“Have a happy holiday, Madeline. Bye.”

As I strap the boys into their carseats, Miles asks me, “Momma, what was that man’s name again? Mr…..”

“Mr. Piazza,” I say as I pull out of the parking space and shift into first.

“Hahahah! I thought you were going to say his name was Mr. PIZZA!”

Miles and Jack are laughing in the back seat, repeating “Mr. Pizza, Mr. Pizza…Oh, do you know the Pizza Man, the Pizza Man, the Pizza Man….”

I shake my head, smiling to myself.

I turn on the radio, those adolescent thoughts still bouncing around my head.

And then I really lose it, listening to the song that haunted me through my teens:

She wants him, so badly, knows what she wants to be

“Pleeeease….dooon’t….staaand…..sooo…..clooose….tooo…..meee.”

sex sex blogs polyamory fantasies

parenting erotica sting the police